State of the Ecosystem

New England 2025

NEFMC

January 09, 2026

State of the Ecosystem (SOE) reporting

Improving ecosystem information and synthesis for fishery managers

Ecosystem indicators linked to management objectives (DePiper et al., 2017)

- Contextual information

- Report evolving since 2016

- Fishery-relevant subset of full Ecosystem Status Reports

Open science emphasis (Bastille et al., 2020)

Used within Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s Ecosystem Process (Muffley et al., 2020)

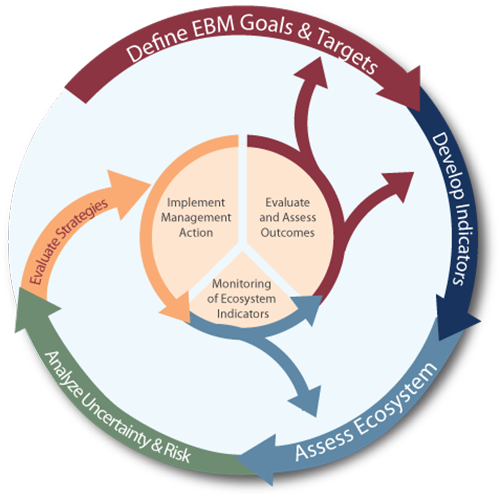

The IEA Loop1

State of the Ecosystem: Maintain 2024 structure for 2025

2025 Report Structure

- Graphical summary

- Page 1 report card re: objectives →

- Page 2 risk summary bullets

- Page 3 2024 snapshot

- Performance relative to management objectives

- Risks to meeting management objectives

- Climate and Ecosystem risks

- Offshore wind development

- 2024 Highlights

Updated Objectives and Risks tables aligning with indicators

Objective categories | Indicators reported |

|---|---|

Objectives: Provisioning and Cultural Services | |

Seafood Production | Landings; commercial total and by feeding guild; recreational harvest |

Commercial Profits | Revenue decomposed to price and volume |

Recreational Opportunities | Angler trips; recreational fleet diversity |

Stability | Diversity indices (fishery and ecosystem) |

Social & Cultural | Community fishing engagement and social vulnerability status |

Protected Species | Bycatch; population (adult and juvenile) numbers; mortalities |

Potential Drivers: Supporting and Regulating Services | |

Management | Stock status; catch compared with catch limits |

Biomass | Biomass or abundance by feeding guild from surveys |

Environment | Climate and ecosystem risk indicators listed in Table 2 |

Risk categories | Observation indicators reported | Potential driver indicators reported |

|---|---|---|

Climate and Ecosystem Risks | ||

Risks to Managing Spatially | Managed species (fish and cetacean) distribution shifts | Benthic and pelagic forage distribution; ocean temperature, changes in currents and cold pool |

Risks to Managing Seasonally | Managed species spawning and migration timing changes | Habitat timing: Length of ocean summer, cold pool seasonal persistence |

Risks to Setting Catch Limits | Managed species body condition and recruitment changes | Benthic and pelagic forage quality & abundance: ocean temperature & acidification |

Other Ocean Uses Risks | ||

Offshore Wind Risks | Fishery revenue and landings from wind lease areas by species and port | Wind development speed; Protected species presence and hotspots |

Ecosystem synthesis themes

Characterizing ecosystem change for fishery management

- Societal, biological, physical and chemical factors comprise the multiple system drivers that influence marine ecosystems through a variety of different pathways.

- Changes in the multiple drivers can lead to regime shifts — large, abrupt and persistent changes in the structure and function of an ecosystem.

- Regime shifts and changes in how the multiple system drivers interact can result in ecosystem reorganization as species and humans respond and adapt to the new environment.

State of the Ecosystem report scale and figures

A glossary of terms (2021 Memo 5), detailed technical methods documentation and indicator data are available online.

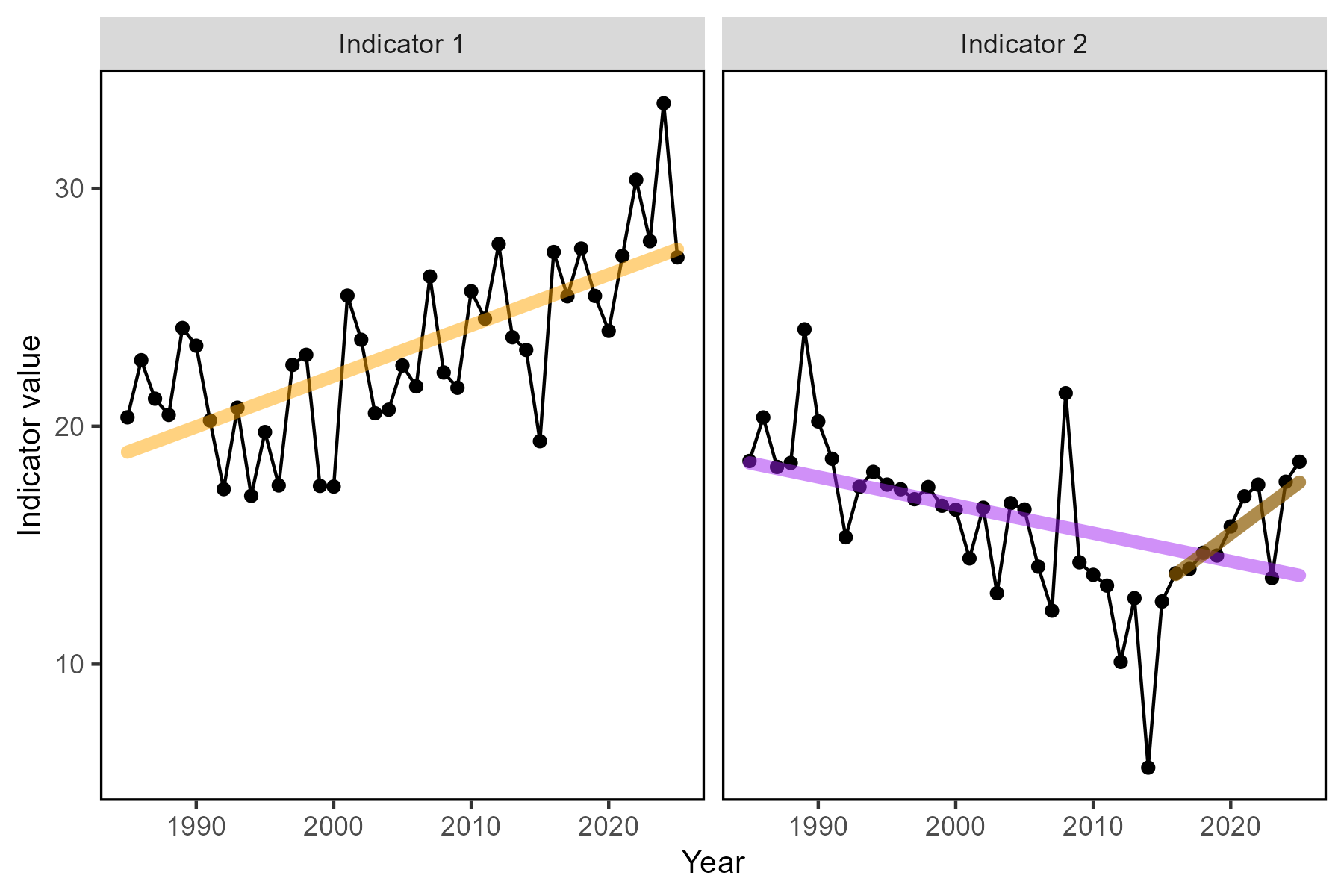

Key to figures

Long-term trends assessed only for 30+ years: more information

Short-term trends assessed for last 10 years of data OR a full time series <30 years

Orange line = significant increase

Purple line = significant decrease

No color line = not significant or < 30 years

Grey background = last 10 years

2025 State of the Ecosystem Request tracking memo: updates noted along the way

Need to add the files

New England State of the Ecosystem Summary 2025:

Performance relative to management objectives - Georges Bank

Seafood production Total  , Managed

, Managed  , Both

, Both

Profits  ,

,

Recreational opportunities: Effort

Effort diversity

Effort diversity

Stability: Fishery not stable; Ecological not stable

Social and cultural:

Fishing engagement and social vulnerability status by community

Revenue climate vulnerability

![mixed trend icon]() , majority medium risk

, majority medium risk

Protected species:

Maintain bycatch below thresholds (harbor porpoise, gray seals)

![mixed trend icon]()

![meeting objectives icon]()

Recover endangered populations

![mixed trend icon]() , NARW

, NARW ![below average icon icon]() Gray seal

Gray seal ![above average icon icon]()

New England State of the Ecosystem Summary 2025:

Performance relative to management objectives - Gulf of Maine

Seafood production  ,

,

Profits Total  ,

,  ; NEFMC managed

; NEFMC managed  ,

,

Recreational opportunities: Effort

Effort diversity

Effort diversity

Stability: Fishery not stable; Ecological not stable

Social and cultural:

Fishing engagement and social vulnerability status by community

Revenue climate vulnerability

![mixed trend icon]() , majority medium risk

, majority medium risk

Protected species:

Maintain bycatch below thresholds (harbor porpoise, gray seals)

![mixed trend icon]()

![meeting objectives icon]()

Recover endangered populations

![mixed trend icon]() , NARW

, NARW ![below average icon icon]() Gray seal

Gray seal ![above average icon icon]() Salmon

Salmon ![below average icon icon]()

State of the Ecosystem Summary 2025:

Risks to meeting fishery management objectives

Climate: risks to managing spatially, managing seasonally, and catch specification

Fish and protected species distribution shifts

Changing spawning and migration timing

Multiple stocks with poor condition, declining productivity

Other ocean uses: offshore wind development

- Current revenue in proposed areas

- 1-32% by New England port

- 1-20% by NEFMC

- Overlap with important right whale foraging habitats, increased vessel strike and noise risks

State of the Ecosystem Summary 2025: 2024 Highlights

Notable 2024 events and conditions

2024 warmest year on record globally. Again.

BUT

Cooler conditions across the coast

Well established Mid Atlantic Cold Pool

Multiple summer upwelling events off NJ

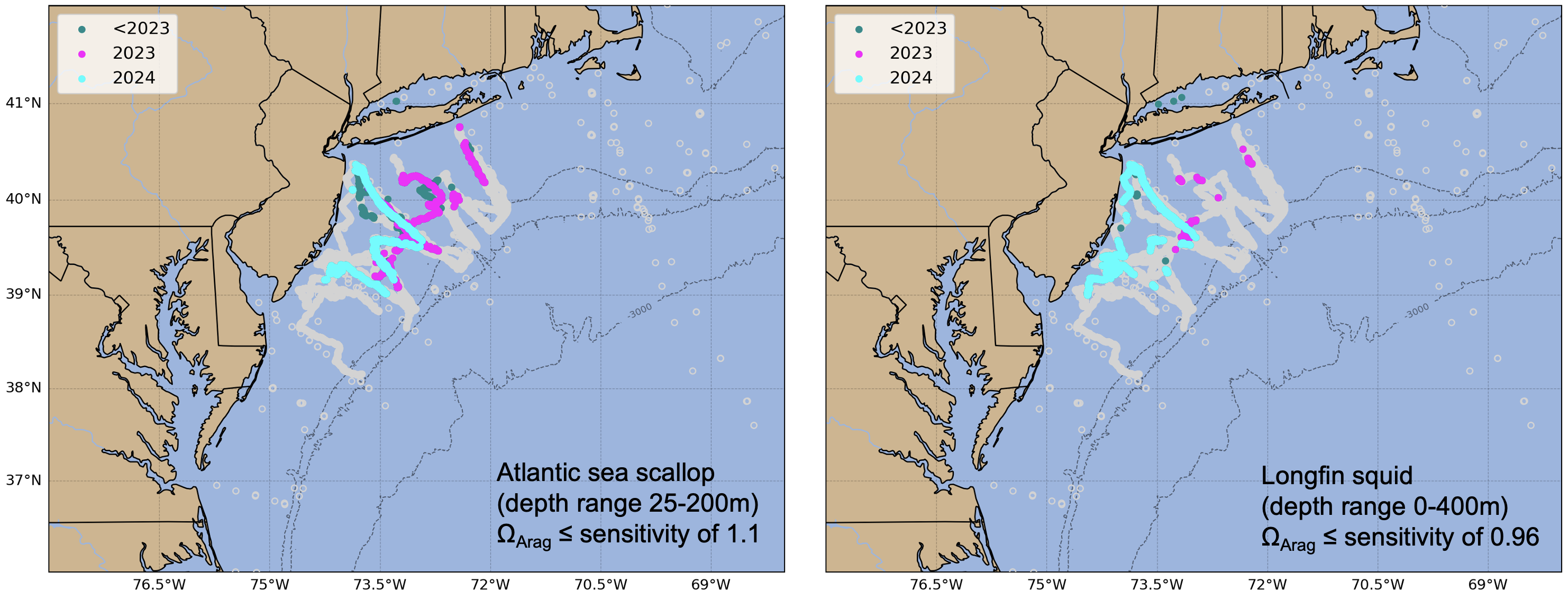

Extreme ocean acidification measured off NJ

Many fishery observations of different spatial and timing patterns, changed abundance

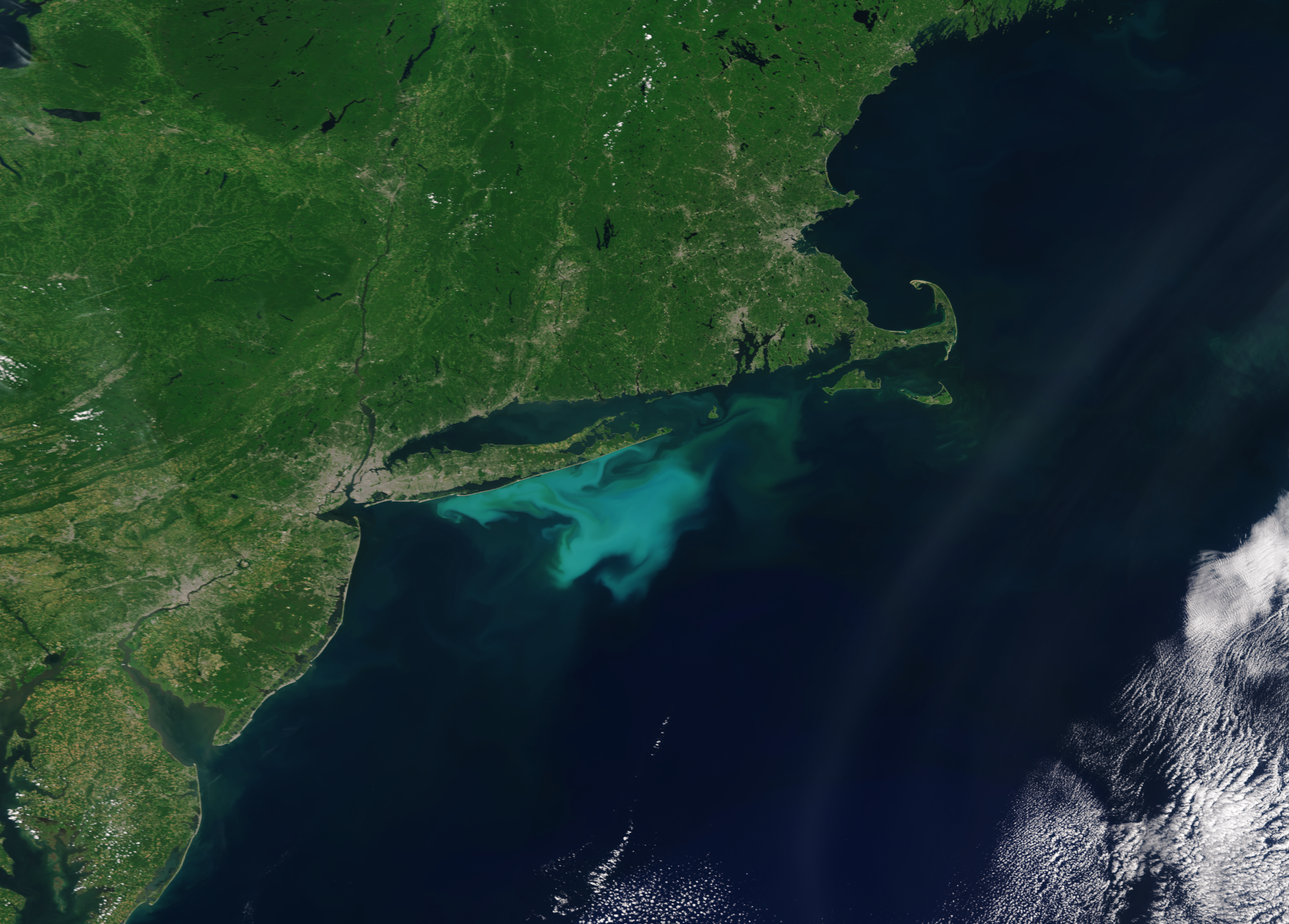

Good scallop recruitment in Nantucket lightship

More red drum in Chesapeake Bay

Arctic copepods in GOM

Cocolithophore bloom off NY

Large whale aggregations

We welcome your observations! northeast.ecosystem.highlights@noaa.gov

2025 Performance relative to management objectives

Objective: New England Seafood production ![decreasing arrow icon]()

![no trend icon]()

![below average icon icon]()

Indicators: Commercial landings, climate risk

Indicators: Recreational harvest

Multiple drivers: ecosystem and stock production, management actions (stock rebuilding), market conditions (including COVID-19 disruptions), and environmental change

New England drivers: Stock status? Survey biomass?

Indicator: Stock status

One more stock below BMSY from last year (S Silver Hake). No change in stocsk below 1/2 BMSY. Stock status and required management actions still likely playing large role in seafood declines.

Indicators: Survey biomass

Biomass availability still seems unlikely driver

Implications: New England Seafood Production

Drivers:

- Decline in commercial landings is most likely driven by actions to rebuild individual stocks (lower quotas) as well as market dynamics

- other drivers affecting recreational landings: tighter shark fishery regulations, changing demographics and preferences of anglers

Monitor:

- Climate risks including warming, ocean acidification, and shifting distributions

- Ecosystem composition and production changes

- Fishing engagement

Objective: New England Commercial Profits ![mixed trend icon]()

![below average icon icon]()

Indicator: Commercial Revenue; profit indicators under SSC review

Both regions dependent on single climate-vulnerable species

Indicator: Bennet–price and volume indices

GOM high revenue despite low volume

Objective: New England Recreational opportunities ![no trend icon]()

![near average icon icon]()

Indicators: Recreational effort and fleet diversity

Implications

- Absence of a long-term trend in recreational effort suggests relative stability in the overall number of recreational opportunities in New England

Objective: New England Fishery Stability: Not Stable

Fishery Indicators: Commercial fleet count, fleet diversity

Fishery Implications:

- Commercial fishery diversity driven by small number of species; less capacity to respond to new opportunities

Fishery Indicators: commercial species revenue diversity, recreational species catch diversity

- Recreational diversity increase due to increase in ASFMC and MAFMC managed species

Objective: New England Ecological Stability ![mixed trend icon]()

![above average icon icon]()

Ecological Indicators: zooplankton diversity (not updated) and total primary production

Ecological Implications:

- Adult diversity in GOM suggests increase in warm-water species

Ecological Indicators: fish richness and traits

- Declines in species fecundity & other life history traits suggests changing ecology

New England Community Social and Climate Vulnerability

Indicators: Commercial fifishery engagement, social vulnerability, revenue climate vulnerability

Time | EPU | Town | Eng | Eng_ct | Rel | Rel_ct | Personal Disruption | Population Composition | Poverty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2022 | NE | New Bedford, MA | 32.873 | 4 | 0.702 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

2022 | NE | Narragansett/Point Judith, RI | 10.842 | 4 | 1.476 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Gloucester, MA | 10.126 | 4 | 0.570 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Portland, ME | 5.870 | 4 | 0.010 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Boston, MA | 5.860 | 4 | -0.109 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

2022 | NE | Port Clyde-Tenants Harbor, ME | 4.940 | 4 | 3.147 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

2022 | NE | Harpswell/Bailey Island, ME | 4.533 | 4 | 1.660 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Chatham, MA | 4.404 | 4 | 5.002 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Stonington, ME | 3.773 | 4 | 10.002 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Friendship, ME | 3.107 | 4 | 4.573 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Implications: Highlighted communities may be vulnerable to changes in fishing patterns due to regulations and/or climate change. When also experiencing social vulnerabilities, they may have lower ability to successfully respond to change.

New England Community Social and Climate Vulnerability

Indicators: Commercial fishery revenue climate vulnerability

The Community Climate Change Risk Indicators are calculated by multiplying the percent contribution of species to the total value landed in a community by their respective Total Vulnerability scores (based on NOAA’s Climate Vulnerability Assessment) for different sensitivity and exposure factors and then summing the resulting values by year.

New England communities shifting towads High/Very High climate vulnerability. Consolidating Species

New England Community Social and Climate Vulnerability

Indicators: Recreational fishery engagement, social vulnerability

Time | EPU | Town | Eng | Eng_ct | Rel | Rel_ct | Personal Disruption | Population Composition | Poverty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2022 | NE | Narragansett/Point Judith, RI | 5.365 | 4 | 0.822 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Barnstable Town, MA | 4.204 | 4 | 0.094 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Old Saybrook, CT | 3.581 | 4 | 0.696 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Newburyport, MA | 3.284 | 4 | 0.292 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Sandwich, MA | 3.280 | 4 | 0.116 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Seabrook, NH | 3.000 | 4 | 0.835 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Waterford, CT | 2.884 | 4 | 0.253 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Hampton, NH | 2.815 | 4 | 0.350 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Westport, MA | 2.499 | 4 | 0.221 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2022 | NE | Harwich Port, MA | 2.460 | 4 | 2.883 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Objectives: Coastwide Protected species Maintain bycatch below thresholds ![mixed trend icon]()

![meeting objectives icon]()

Indicators: Harbor porpoise and gray seal bycatch

Implications:

Currently meeting objectives, but uncertainty in gray seal estimates

The downward trend in harbor porpoise bycatch can also be due to a decrease in harbor porpoise abundance in US waters, reducing their overlap with fisheries, and a decrease in gillnet effort.

Gray seal among the highest bycatch of any U.S. marine mammal. The increasing trend in gray seal bycatch may be related to an increase in the gray seal population (U.S. pup counts).

Objectives: Coastwide Protected species Recover endangered populations ![decreasing arrow icon]()

![below average icon icon]()

Indicators: North Atlantic right whale population, calf counts

Implications:

Signs the adult population stabilized 2020-2023

Population drivers for North Atlantic Right Whales (NARW) include combined fishery interactions/ship strikes, distribution shifts, and copepod availability.

Additional potential stressors include offshore wind development, which overlaps with important habitat areas used year-round by right whales, including mother and calf migration corridors and foraging habitat.

Unusual mortality events continue for 3 large whale species.

2025 Risks to meeting fishery management objectives

Revised Risks: Climate and Ecosystem Change

Risk categories | Observation indicators reported | Potential driver indicators reported |

|---|---|---|

Climate and Ecosystem Risks | ||

Risks to Managing Spatially | Managed species (fish and cetacean) distribution shifts | Benthic and pelagic forage distribution; ocean temperature, changes in currents and cold pool |

Risks to Managing Seasonally | Managed species spawning and migration timing changes | Habitat timing: Length of ocean summer, cold pool seasonal persistence |

Risks to Setting Catch Limits | Managed species body condition and recruitment changes | Benthic and pelagic forage quality & abundance: ocean temperature & acidification |

Other Ocean Uses Risks | ||

Offshore Wind Risks | Fishery revenue and landings from wind lease areas by species and port | Wind development speed; Protected species presence and hotspots |

Risks to Managing Spatially

Potential Impacts: Spatial misallocation of quotas within and across jurisdictions, leading to unmet quotas and/or increased discards. Specification of gear management areas may not utilize quotas and minimize bycatch.

Risks to Managing Seasonally

Potential Impacts: Spawning closures are less effective if peak spawning occurs outside the seasonal closure. Seasonal openings of exemption areas may be inconsistent with species presence. Seasonal quota allocations may be misaligned with availability.

Risks to Setting Catch Limits

Potential Impacts: Changes in environmental conditions can affect stock reference points and short-term stock projections. When productivity changes are not accounted for, they can lead to misspecified quotas and rebuilding plans.

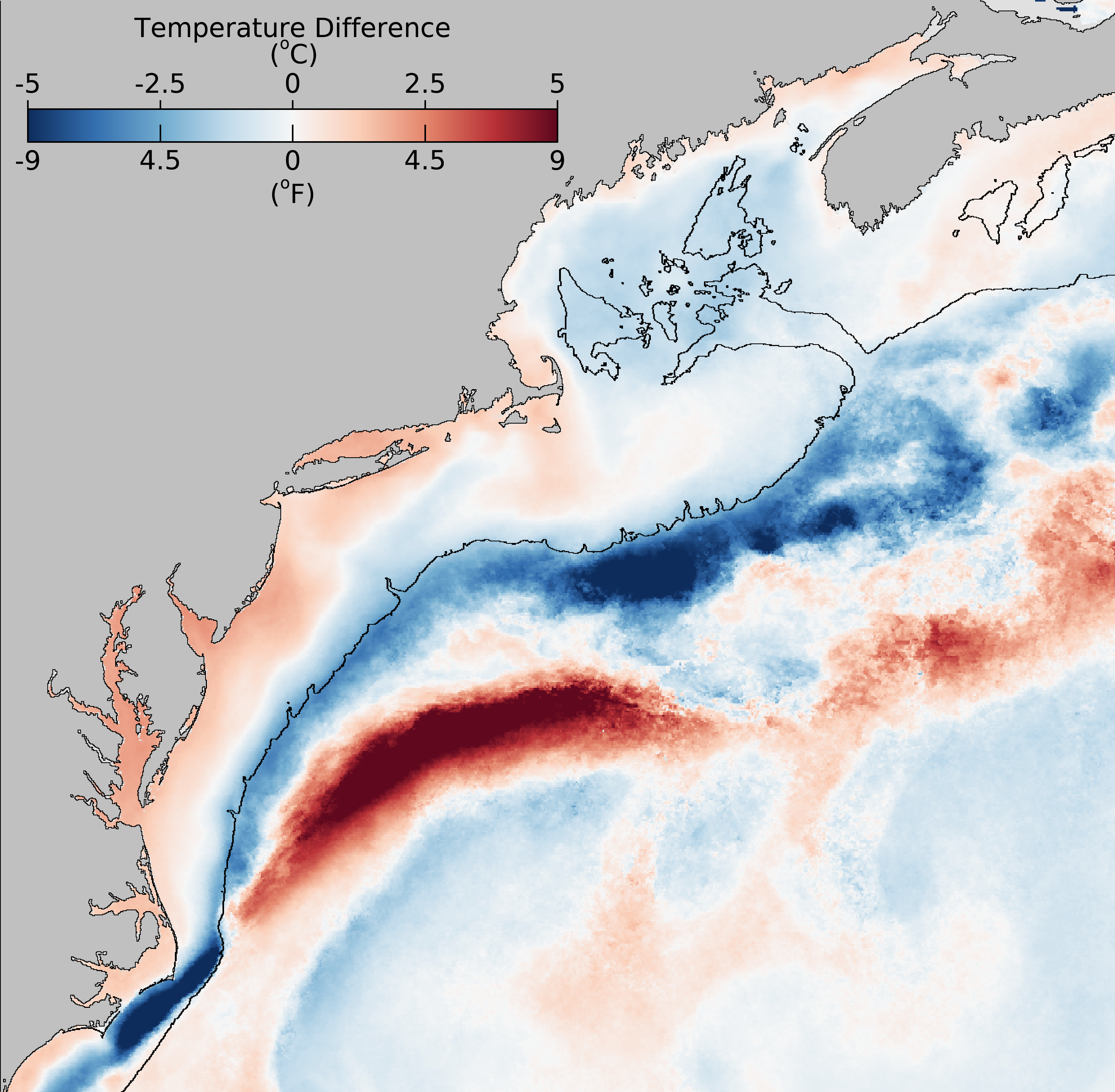

Risks to Managing Spatially: Coastwide

Indicators: Fish distribution shifts

Cetacean distribution shifts

Risks to Managing Spatially: Coastwide

Drivers: changing ocean habitat

Cold pool temperature and spatial extent

New Spatial Shift Indicators: Benthos, Zooplankton

Benthos center of gravity from fish stomachs

Copepods center of gravity from ECOMON

Risks to Managing Spatially: Coastwide

Future considerations

Distribution shifts caused by changes in thermal habitat and ocean circulation are likely to continue as long as long-term trends persist. Episodic and short-term events (see 2024 Highlights) may increase variability in the trends, however species distributions are unlikely to reverse to historical ranges in the short term. Increased mechanistic understanding of distribution drivers is needed to better understand future distribution shifts: species with high mobility or short lifespans react differently from immobile or long lived species.

Long-term oceanographic projections forecast a temporary pause in warming over the next decade due to internal variability in circulation and a southward shift of the Gulf Stream. Near-term forecasts are being evaluated to determine how well they are able to predict episodic and anomalous events that are outside of the long-term patterns.

Adapting management to changing stock distributions and dynamic ocean processes will require continued monitoring of populations in space and evaluating management measures against a range of possible future spatial distributions. Processes like the East Coast Climate Scenario Planning, and subsequent formation of the East Coast Climate Coordination Group, can help coordinate management.

Risks to Managing Seasonally: Coastwide

Indicators: spawning timing, migration change

Recreational tuna fisheries 50 days earlier in the year in 2019 compared to 2002.

In Cape Cod Bay, peak spring habitat use by right and humpback whales has shifted 18-19 days later over time.

Baseline information on large whale seasonal presence has been collected.

Risks to Managing Seasonally: New England

Drivers: thermal transition, habitat persistence, bloom timing

Future considerations

Management actions that rely on effective alignment of fisheries availability and biological processes should continue to evaluate whether prior assumptions on seasonal timings still hold.

New indicators should be developed to monitor timing shifts for stocks.

Bloom timing

Risks to Setting Catch Limits: New England

Indicator: Fish productivity

Risks to Setting Catch Limits: New England

Indicator: Condition

Risks to Setting Catch Limits: New England Drivers

Drivers: Forage Quality and Abundance

New indicators: benthos abundance

Risks to Setting Catch Limits: New England Drivers

Drivers: Low trophic levels

Risks to Setting Catch Limits: Coastwide

Drivers: Environmental

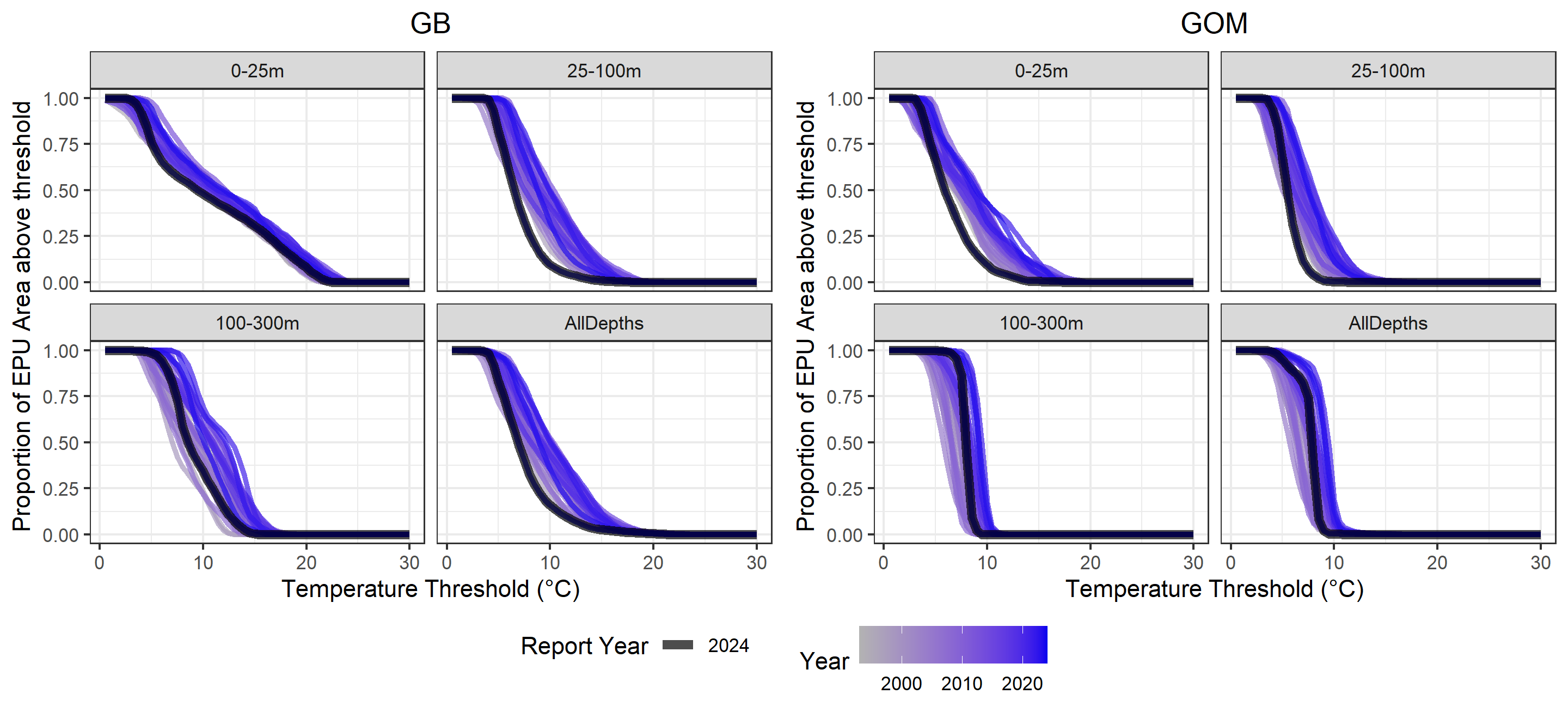

2024 Thermal habitat area by depth

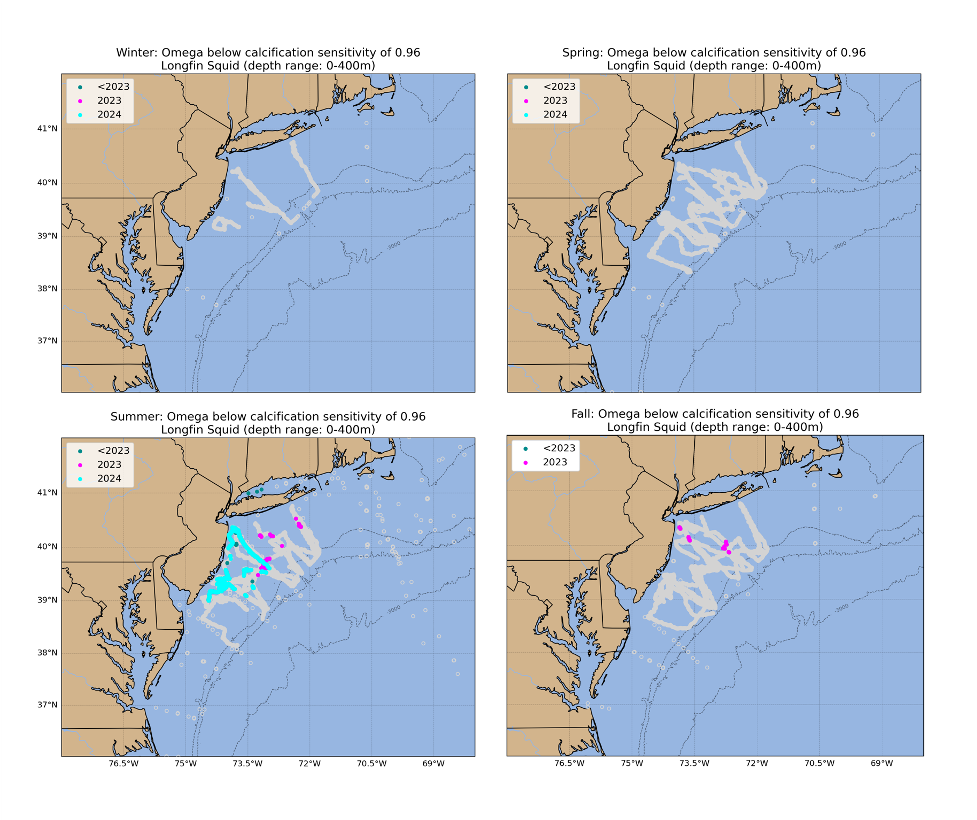

Risks to Setting Catch Limits: Coastwide

Drivers: Environmental Potential Ocean Acidification Impacts: Scallops and Longfin squid

Drivers: Predation

Seals increasing, mix of population status for HMS

Risks to Setting Catch Limits

Future considerations

Processes that control fish productivity and mortality are dynamic, complex, and are the result of the interactions between multiple changing system drivers.

There is a real risk that short-term predictions in assessments and rebuilding plans that assume unchanging underlying conditions will not be as effective, given the observed change documented in the prior sections in both ecological and environmental processes.

Assumptions for species’ growth, reproduction, and natural mortality should continue to be evaluated for individual species.

With observations of system-wide productivity shifts of multiple managed stocks, more research is needed to determine whether regime shifts or ecosystem reorganization are occurring, and how this should be incorporated into management.

Risks: Offshore Wind Development New England

Indicators: fishery and community specific revenue in lease areas

Council request: Mid-Atlantic ports relying on New England managed species

Risks: Offshore Wind Development: Implications

Implications:

Current plans for buildout of offshore wind in a patchwork of areas spreads the impacts differentially throughout the region.

Lease areas overlap with North Atlantic right whale habitat. Development may alter local oceanography and prey availability, increase vessel strike risk, and result in pile driving noise impacts.

2024 Highlights: Methods

Observations solicited from:

- SOE contributors

- NEFSC colleagues

- Academic colleagues

- Management partners

- Fishing industry

We welcome your observations! northeast.ecosystem.highlights@noaa.gov

Observations included if:

- Record high or low observations

- Different from recent conditions

- Reported by multiple sources

- Affecting fishery operations

- Newsworthy

Not exhaustive list; Full impacts remain to be seen

Reprinted from Cape Cod Commercial Fisherman’s Alliance February 2025 Newsletter →

2024 Highlights: generally cooler, fresher Northeast Shelf

Globally, 2024 warmest year on record (above previous record 2023)

BUT, nearly all NE shelf seasonal surface and bottom temperatures back to longer term average

2023-2024 data suggest more Labrador slope water into the GOM (Record et al., 2024)

Linked to well-developed 2024 Mid Atlantic Cold Pool

2024 Highlights

Extreme observation of ocean acidification risk off NJ

Multiple summer upwelling events off NJ

Unusual timing, location, abundance:

Fishery observations

- Delayed migration of longfin squid, black sea bass, haddock

- Unusual locations for pollock, bluefin tuna, Atlantic mackerel, longfin squid, bluefish, and bonito

- Local abundance of Atlantic mackerel

- Record catches of red drum in Chesapeake Bay

Good scallop recruitment in Nantucket lightship

Arctic copepods in GOM

Cocolithophore bloom off NY

Large whale aggregations

THANK YOU! SOEs made possible by (at least) 88 contributors from 20+ institutions

Andrew Applegate (NEFMC)

Kimberly Bastille

Aaron Beaver (Anchor QEA)

Andy Beet

Brandon Beltz

Ruth Boettcher (Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries)

Mandy Bromilow (NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office)

Joseph Caracappa

Samuel Chavez-Rosales

Baoshan Chen (Stony Brook University)

Zhuomin Chen (UConn)

Doug Christel (GARFO)

Patricia Clay

Lisa Colburn

Jennifer Cudney (NMFS Atlantic HMS Management Division)

Tobey Curtis (NMFS Atlantic HMS Management Division)

Art Degaetano (Cornell U)

Geret DePiper

Bart DiFiore (GMRI)

Emily Farr (NMFS Office of Habitat Conservation)

Michael Fogarty

Paula Fratantoni

Kevin Friedland

Marjy Friedrichs (VIMS)

Sarah Gaichas

Ben Galuardi (GAFRO)

Avijit Gangopadhyay (SMAST UMass Dartmouth)

James Gartland (VIMS)

Lori Garzio (Rutgers University)

Glen Gawarkiewicz (WHOI)

Laura Gruenburg

Sean Hardison

Dvora Hart

Cliff Hutt (NMFS Atlantic HMS Management Division)

Kimberly Hyde

John Kocik

Steve Kress (National Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program)

Young-Oh Kwon (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Scott Large

Gabe Larouche (Cornell U)

Daniel Linden

Andrew Lipsky

Sean Lucey (RWE)

Don Lyons (National Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program)

Chris Melrose

Anna Mercer

Shannon Meseck

Ryan Morse

Ray Mroch (SEFSC)

Brandon Muffley (MAFMC)

Robert Murphy

Kimberly Murray

NEFSC staff

David Moe Nelson (NCCOS)

Chris Orphanides

Richard Pace

Debi Palka

Tom Parham (Maryland DNR)

CJ Pellerin (NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office)

Charles Perretti

Kristin Precoda

Grace Roskar (NMFS Office of Habitat Conservation)

Jeffrey Runge (U Maine)

Grace Saba (Rutgers University)

Vincent Saba

Sarah Salois

Chris Schillaci (GARFO)

Amy Schueller (SEFSC)

Teresa Schwemmer (URI)

Tarsila Seara

Dave Secor (CBL)

Emily Slesinger

Angela Silva

Adrienne Silver (UMass/SMAST)

Talya tenBrink (GARFO)

Abigail Tyrell

Rebecca Van Hoeck

Bruce Vogt (NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office)

Ron Vogel (University of Maryland Cooperative Institute for Satellite Earth System Studies and NOAA/NESDIS Center for Satellite Applications and Research)

John Walden

Harvey Walsh

Sarah Weisberg

Changhua Weng

Dave Wilcox (VIMS)

Timothy White (Environmental Studies Program BOEM)

Sarah Wilkin (NMFS Office of Protected Resources)

Mark Wuenschel

Qian Zhang (U Maryland)

References

Bastille, K. et al. (2020). “Improving the IEA Approach Using Principles of Open Data Science”. In: Coastal Management 0.0. Publisher: Taylor & Francis _eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155, pp. 1-18. ISSN: 0892-0753. DOI: 10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846155 (visited on Dec. 09, 2020).

DePiper, G. S. et al. (2017). “Operationalizing integrated ecosystem assessments within a multidisciplinary team: lessons learned from a worked example”. En. In: ICES Journal of Marine Science 74.8, pp. 2076-2086. ISSN: 1054-3139. DOI: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx038. URL: https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/74/8/2076/3094701 (visited on Mar. 09, 2018).

Muffley, B. et al. (2020). “There Is no I in EAFM Adapting Integrated Ecosystem Assessment for Mid-Atlantic Fisheries Management”. In: Coastal Management 0.0. Publisher: Taylor & Francis _eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156, pp. 1-17. ISSN: 0892-0753. DOI: 10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1846156 (visited on Dec. 09, 2020).

Record, N. R. et al. (2024). “Early Warning of a Cold Wave in the Gulf of Maine”. In: Oceanography 37.3, pp. 6-9. DOI: 10.5670/oceanog.2024.506. URL: https://tos.org/oceanography/article/early-warning-of-a-cold-wave-in-the-gulf-of-maine (visited on Mar. 04, 2025).

Additional resources

Slides available at https://nefsc.github.io/READ-EDAB-SOE_reports/

- Contact: joseph.caracappa@noaa.gov

, majority medium risk

, majority medium risk